The following article is intended for the do-it-yourselfer that is interested in either finding and fixing a problem with a barrel, or improving the accuracy of an already good performer. You don't have to be a master machinist to get excellent results. The techniques described here can be done with simple tools like a Dremel and handheld drill. So with that said, here we go...

First off, a short pre-flight inspection...

Before you start removing metal

I like to start by giving the barrel an inspection to get an idea of what I'm working with:

Push a pellet through the barrel from breech to muzzle. We're looking for possible issues in 4 areas:

Continuing on, note any loose or tight spots along the barrel's length. What I'm wanting is a pretty consistent, light resistance all the way through...that is, unless the muzzle is choked. Lastly, pay close attention to resistance just as the head and skirt reach the crown and emerge into the world. Hanging up here is an indication of a burr left after crowning that will need to be dealt with. BTW, distinguishing between a choked barrel and a burr at the crown normally is fairly easy. In a choked barrel you'll encounter resistance for the last inch or so. If the crown has a burr, you'll hit a snag just as the pellet comes out the end.

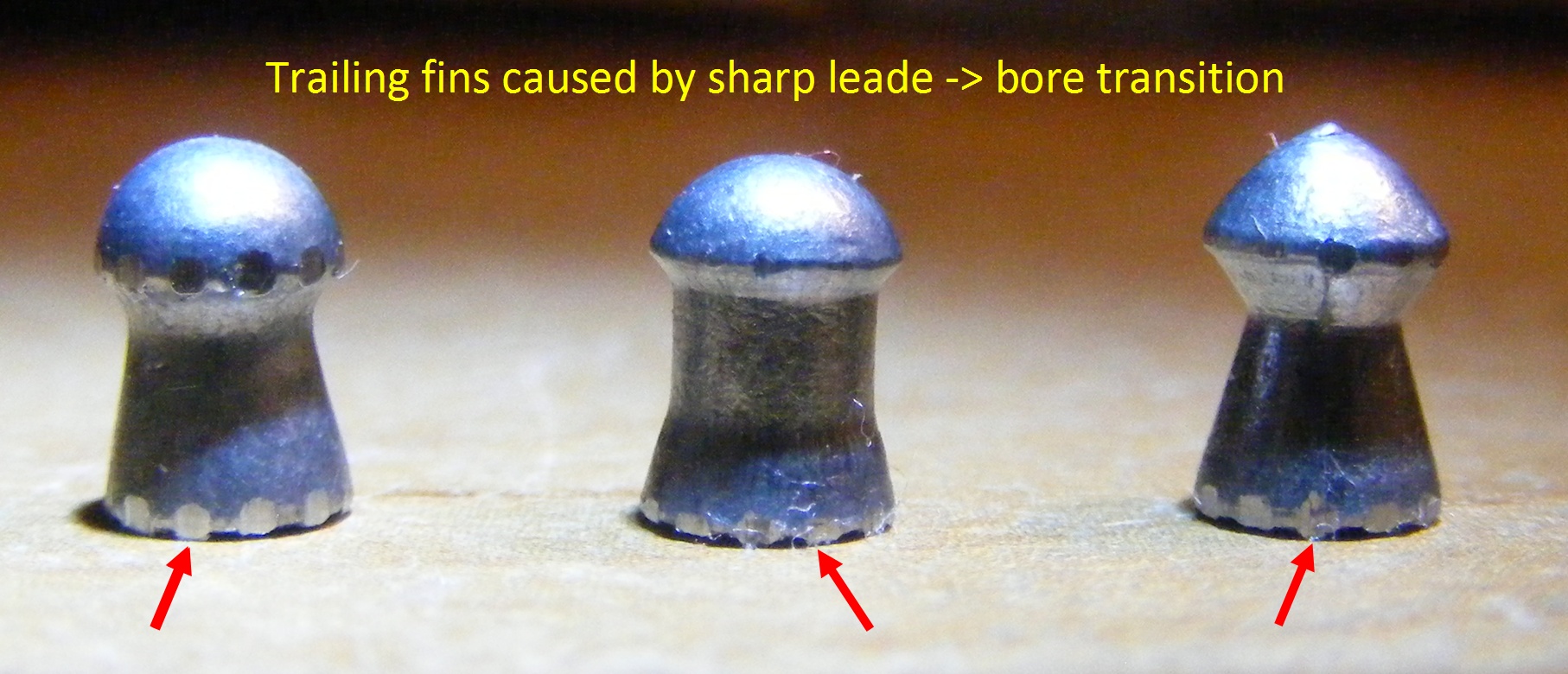

inspect the pellet - Now inspect the pellet(s) with the help of some magnification. Damage in a confined spot around the perimeter of the skirt usually indicates a burr at the barrel port. Smearing of the skirt where it met the rifling usually indicates a sharp edge at the leade->bore transition. Slight rifling marks around the head are a good indication that the pellet is a good fit for the barrel...enough to prevent yawing as it hurtles down the bore but not so much that it damages the head. By contrast, rifling engagement of the skirt should be deeper because the skirt is a larger diameter by a few thousandths.

Now with some expectation of what you have to deal with, on with the barrel treatments...

Down to business

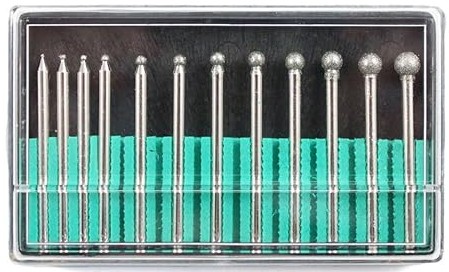

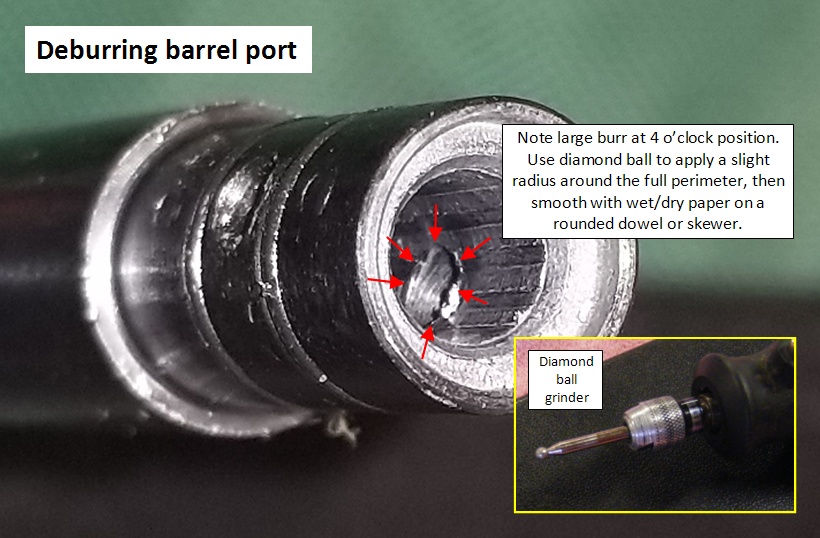

1. deburr the barrel port - Use a small diamond ball burr to radius the edges of the barrel port. An assortment like this runs about $10:

What I do is load a 3/32" (for .177 cal) or 1/8" (for .22 cal or larger) diameter ball into the Dremel running at its lowest speed, and work it from inside the hole and up over the sharp edge all the way around the perimeter of the hole. Don't go crazy with it; the radius need only be five or ten thousandths (0.005" - 0.010"). Just trying to get rid of the wire edge left from the drilling operation. Then take a small dowel or skewer wrapped in 400 or 600 grit to smooth the newly-formed radius, followed by 1000 or 1200 grit. Apply some light oil to help shed the swarf. Since this work is done at a shallow angle, round over the end of the dowel so it can dip into the hole as you pass it back and forth. Expect to chew up the paper a couple of times; just keep refreshing the abrasive and work it until it is smooth. It will become apparent when you've done enough because the paper will no longer be as apt to shred.

Refer to the following photo courtesy of Tom/UlteriorModem.

While we're at it, notice the remnants of the rifling and general surface roughness in the photo above. These are indications of an inadequately prepared leade. This region will benefit from being worked smooth, which brings us to the next thing.

2. treat the leade->bore transition - A picture is in order: (thanks to Kirby/K.O.)

Knock down the sharp transition between the leade and the bore. As with the barrel port, a regimen of 400-600 grit followed by 1000-1200 is good for this operation. Wrap the paper around a small dowel and sweep it in and out, applying pressure all around the perimeter. The goal here is to help the pellet ease into the rifling without being scored by a sharp leading edge.

Some guys prefer to instead use a Cratex point for this operation. These grinding/polishing bits are a rubber material impregnated with abrasive. Cratex is the popular brand name; generics are also readily available. What you do is first spin it against a piece of sandpaper until it is a snug fit to the leade. In this way, it smooths the leade and applies a bevel to the leading edge of the rifling...all in one go. Very quick and effective, just be careful not to remove more material than is necessary. It's easy to do with power tools.

My advice to beginners is the dowel approach because you can feel when you've done enough.

3. polish the bore - This process removes microscopic surface fretting from the bore, which helps to extend cleaning intervals (lead will not abrade and stick to the walls as readily) and reduces a barrel's propensity to throw fliers. Some indicate it also makes a barrel less pellet fussy. Things you will need:

J-B bore paste

Deburring riflings - JB Bore Paste

4. touch up the crown - Firstly, there are many different geometries that can be applied to a crown but most air rifle barrels will have a simple chamfer so that's what I will focus on. Give the crown a closeup visual inspection. If the chamfer is a uniform width all the way around the perimeter, a little touchup with a brass screw will do. What you will need is a round head (not pan head) brass machine screw. #6-32 is good for .177 cal and a #8-32 is good for .22 and .25 cal. Whereas most everything that has been discussed thus far should be done with the barrel removed, you can do this procedure with the barrel installed. Secure the barrel in an upright position so you can have both hands free. Stuff a small piece of cotton into the muzzle to keep debris from falling down into the barrel. Chuck up the screw into a handheld drill. Coat the head of the screw in polishing compound and hold it against the muzzle and operate the drill at low speed, moving it in an irregular circular or figure 8 pattern. I use the term "pattern" loosely; you expressly want to randomize the movements. If you try to hold the drill in one position, invariably more pressure will be applied to one side which will abrade an irregular bevel into the crown.

Do not apply downward pressure to speed things along. If you do, a wire edge will get pushed into the bore. I don't even use the full weight of my drill; I support it to limit the pressure to something between 0.5 and 1 pound. The idea is to let the abrasive slowly do the work. Refresh it often and keep at it until you see a clean, polished ring appear. A good crown will also have a distinct cog-like appearance when viewed under magnification, owing this to sharp, burr-free lands and grooves. Here's a before and after for reference...hopefully your before won't be this bad:

When you think you've done enough, check that there is no burr remaining. The usual way is to very gently drag a cotton swab over the crown (from inside the bore and onto the bevel) and see if it snags. If it does, you still have a burr that needs to be worked down. When dealing with an unchoked barrel, I like to check by pushing a pellet through from breech to muzzle. I find it easier to detect a slight burr this way. I know it's right when the head of the pellet slips out the end with no more resistance than it takes to push it down the barrel.

If the chamfer is irregular, the end of the barrel will need to be reworked. If you can have someone with a lathe do it for you, that is probably best for most weekend warriors but if you are confident in your abilities, you can chop and recrown on your own. Here is a link to my DIY crowning guide using a drill press to achieve a nice square crown without a lathe. There are many different ways to go about it and some good videos can be found by searching youtube.

Here's an example of an irregular chamfer, before and after:

Checking your work

After all the work has been completed, I like to use compressed air to blow away any loose and/or heavy debris, then run a few cleaning patches through the barrel. Then I slug the barrel again, looking for any remaining trouble spots. If all looks good, back on the gun it goes and then off to shoot groups with various pellets to see what it likes.

First off, a short pre-flight inspection...

Before you start removing metal

I like to start by giving the barrel an inspection to get an idea of what I'm working with:

Push a pellet through the barrel from breech to muzzle. We're looking for possible issues in 4 areas:

- barrel port

- leade->bore transition

- bore

- crown

Continuing on, note any loose or tight spots along the barrel's length. What I'm wanting is a pretty consistent, light resistance all the way through...that is, unless the muzzle is choked. Lastly, pay close attention to resistance just as the head and skirt reach the crown and emerge into the world. Hanging up here is an indication of a burr left after crowning that will need to be dealt with. BTW, distinguishing between a choked barrel and a burr at the crown normally is fairly easy. In a choked barrel you'll encounter resistance for the last inch or so. If the crown has a burr, you'll hit a snag just as the pellet comes out the end.

inspect the pellet - Now inspect the pellet(s) with the help of some magnification. Damage in a confined spot around the perimeter of the skirt usually indicates a burr at the barrel port. Smearing of the skirt where it met the rifling usually indicates a sharp edge at the leade->bore transition. Slight rifling marks around the head are a good indication that the pellet is a good fit for the barrel...enough to prevent yawing as it hurtles down the bore but not so much that it damages the head. By contrast, rifling engagement of the skirt should be deeper because the skirt is a larger diameter by a few thousandths.

Now with some expectation of what you have to deal with, on with the barrel treatments...

Down to business

1. deburr the barrel port - Use a small diamond ball burr to radius the edges of the barrel port. An assortment like this runs about $10:

What I do is load a 3/32" (for .177 cal) or 1/8" (for .22 cal or larger) diameter ball into the Dremel running at its lowest speed, and work it from inside the hole and up over the sharp edge all the way around the perimeter of the hole. Don't go crazy with it; the radius need only be five or ten thousandths (0.005" - 0.010"). Just trying to get rid of the wire edge left from the drilling operation. Then take a small dowel or skewer wrapped in 400 or 600 grit to smooth the newly-formed radius, followed by 1000 or 1200 grit. Apply some light oil to help shed the swarf. Since this work is done at a shallow angle, round over the end of the dowel so it can dip into the hole as you pass it back and forth. Expect to chew up the paper a couple of times; just keep refreshing the abrasive and work it until it is smooth. It will become apparent when you've done enough because the paper will no longer be as apt to shred.

Refer to the following photo courtesy of Tom/UlteriorModem.

While we're at it, notice the remnants of the rifling and general surface roughness in the photo above. These are indications of an inadequately prepared leade. This region will benefit from being worked smooth, which brings us to the next thing.

2. treat the leade->bore transition - A picture is in order: (thanks to Kirby/K.O.)

Knock down the sharp transition between the leade and the bore. As with the barrel port, a regimen of 400-600 grit followed by 1000-1200 is good for this operation. Wrap the paper around a small dowel and sweep it in and out, applying pressure all around the perimeter. The goal here is to help the pellet ease into the rifling without being scored by a sharp leading edge.

Some guys prefer to instead use a Cratex point for this operation. These grinding/polishing bits are a rubber material impregnated with abrasive. Cratex is the popular brand name; generics are also readily available. What you do is first spin it against a piece of sandpaper until it is a snug fit to the leade. In this way, it smooths the leade and applies a bevel to the leading edge of the rifling...all in one go. Very quick and effective, just be careful not to remove more material than is necessary. It's easy to do with power tools.

My advice to beginners is the dowel approach because you can feel when you've done enough.

3. polish the bore - This process removes microscopic surface fretting from the bore, which helps to extend cleaning intervals (lead will not abrade and stick to the walls as readily) and reduces a barrel's propensity to throw fliers. Some indicate it also makes a barrel less pellet fussy. Things you will need:

- cleaning rod - Important that it be a good double ball bearing cleaning rod to ensure the cleaning pellet/wad/patch follows the riflings

- rod adapter - Brownell's VFG stuff is recommended for .22 cal and above. Specifically, the 084-000-002WB adapter. For .177, use a jag and cotton patches.

- cleaning pellets - firm felt pellets for Brownell's VFG system such as part number 610 for .22 cal.

- abrasive - A fine friable abrasive like J-B Bore Paste, home-brew slurry of diatomaceous earth, or similar (around 1000 grit)

- lubricant - Kano Kroil seems to be preferred but another light oil can be substituted. Its role is to help float away the swarf.

J-B bore paste

Deburring riflings - JB Bore Paste

4. touch up the crown - Firstly, there are many different geometries that can be applied to a crown but most air rifle barrels will have a simple chamfer so that's what I will focus on. Give the crown a closeup visual inspection. If the chamfer is a uniform width all the way around the perimeter, a little touchup with a brass screw will do. What you will need is a round head (not pan head) brass machine screw. #6-32 is good for .177 cal and a #8-32 is good for .22 and .25 cal. Whereas most everything that has been discussed thus far should be done with the barrel removed, you can do this procedure with the barrel installed. Secure the barrel in an upright position so you can have both hands free. Stuff a small piece of cotton into the muzzle to keep debris from falling down into the barrel. Chuck up the screw into a handheld drill. Coat the head of the screw in polishing compound and hold it against the muzzle and operate the drill at low speed, moving it in an irregular circular or figure 8 pattern. I use the term "pattern" loosely; you expressly want to randomize the movements. If you try to hold the drill in one position, invariably more pressure will be applied to one side which will abrade an irregular bevel into the crown.

Do not apply downward pressure to speed things along. If you do, a wire edge will get pushed into the bore. I don't even use the full weight of my drill; I support it to limit the pressure to something between 0.5 and 1 pound. The idea is to let the abrasive slowly do the work. Refresh it often and keep at it until you see a clean, polished ring appear. A good crown will also have a distinct cog-like appearance when viewed under magnification, owing this to sharp, burr-free lands and grooves. Here's a before and after for reference...hopefully your before won't be this bad:

When you think you've done enough, check that there is no burr remaining. The usual way is to very gently drag a cotton swab over the crown (from inside the bore and onto the bevel) and see if it snags. If it does, you still have a burr that needs to be worked down. When dealing with an unchoked barrel, I like to check by pushing a pellet through from breech to muzzle. I find it easier to detect a slight burr this way. I know it's right when the head of the pellet slips out the end with no more resistance than it takes to push it down the barrel.

If the chamfer is irregular, the end of the barrel will need to be reworked. If you can have someone with a lathe do it for you, that is probably best for most weekend warriors but if you are confident in your abilities, you can chop and recrown on your own. Here is a link to my DIY crowning guide using a drill press to achieve a nice square crown without a lathe. There are many different ways to go about it and some good videos can be found by searching youtube.

Here's an example of an irregular chamfer, before and after:

Checking your work

After all the work has been completed, I like to use compressed air to blow away any loose and/or heavy debris, then run a few cleaning patches through the barrel. Then I slug the barrel again, looking for any remaining trouble spots. If all looks good, back on the gun it goes and then off to shoot groups with various pellets to see what it likes.